A walk through the old pastry shops of downtown Tehran

“The Armenians, the Turks and the Greeks all claim to have invented Turkish coffee.”

“So who was it, really?” I ask.

“The Armenians of course!” he retorts loudly, his eyeballs popping out, as if shocked that I would even ponder the question.

Meet the owner of Lord Confectionary in Villa Street, downtown Tehran, just across from St Sarkis Cathedral. Today, the area is mostly handicraft tourist stores, and many buildings have been bought by Payam-e Noor (distance learning) University. Two decades ago, this section of the street was mainly residential and one of Tehran’s Armenian quarters.

Stepping into Lord through the white metal door, you see a small flight of stairs to your left, which leads up to the café’s sitting area, where signs on the walls remind “dear guests” to sit no longer than 30 minutes. The rule is enforced only during busy hours.

Iran pastry shops Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Lord Confectionary, Villa Street, Tehran Photograph: The Tehran Bureau

The main floor is where the pastries and cakes are sold. In recent years, quality has declined. When Maggie, the feisty manager, was here, she held onto the older pastry chefs and bakers. Once she left, the cookie crumbled, so to speak.

We keep coming to Lord not for the quality of the pastries, but for the whiff of nostalgia. Also, the apricot tarts aren’t too bad, and the store offers a variety of cakes, tarts, cookies and pirogi made with unusually light Danish-pastry dough.

Tehranis do not take their pastries lightly – literally. Baked goods are sold in boxes of a minimum 500g (1.1lb) going all the way to 2kg (4.4lb). It isn’t strange to see someone walking out carrying several boxes heaped in a precarious pile.

The Iranian palette is no stranger to sweets – from the haji badomi (sugary almond balls) of Yazd to the kolompeh (crisp, date-stuffed cookies) of Kerman. But Tehran has managed to take the European pastry and make its own, a bread pastry that is the perfect complement to afternoon tea.

Lalezar district in Tehran

Lalezar in the 1960s Photograph: ShahreFarang.com

“Armenians introduced Tehran to the European pastry,” the owner of Lord tells me. His father opened the shop in 1964, he explains, decades after Tehran’s first Armenian pastry store was opened in the bustling, now almost mythical Lalehzar Street. “They packed up and left for the United States after the revolution, but we had thick skin.”

There is no shortage of good pastry shops in downtown. Upscale bakeries have taken over in north Tehran, but this is still the Mecca of shirini (baked sweets). Walking a few minutes south from Lord, on Taleqani Street you will find one of Tehran’s best pastry stores: Shirini Danmarki (Danish Pastry), where the pastries have undergone an Iranian metamorphosis.

Danish pastry Tehran Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Danish Pastry shop, Tehran Photograph: The Tehran Bureau

The shop offers custard or apricot jam in a buttery crust, apple filled tarts, and Iranian style puff pastry. People come in especially on the half hour (from 8:30 am onward) as the famed noon danmarki – slices of flaky bread stuffed with their own special crème patisserie and sprinkled with sugar – emerges fresh from the oven.

I ask the lady behind the counter if I can apply to intern in the kitchen, but she only looks at me with wide eyes. “With 17 sibiloo (mustached) male labourers?” she asks. The city’s pastry empire is dominated by mardhayeh kargar (male labourers), who you would never imagine could make a butter crust so flaky and light. She lets me peek into their kitchen, where more than a dozen heavily-bellied men are painstakingly preparing dough or custard, or putting the finishing touches on a cake.

For me, an ideal day is roaming downtown’s old districts, then stopping at Danish Pastry for sweets. Then, going for lunch at Soren, an Armenian sandwich store located between Danish and Lord at the intersection of Villa and Warsaw streets: it has been making sumptuous, reasonably priced steak sandwiches sprinkled with diced herbs for generations of downtown dwellers. Then, back to Lord for coffee. Or the whole ritual can be practised in reverse.

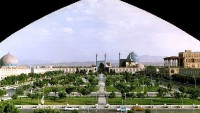

Iran pastry shops Facebook Twitter Pinterest

A whiff of the past, Hans’ garden, Tehran Photograph: The Tehran Bureau

West of Lord, on Aban street, in a quaint corner with old houses, stands Hans Bakery. If you didn’t notice the sign on the green door, you’d mistake it for another home. Inside, there are flowers in the yard, and from the kitchen comes the sound of banging pots and pans. The sweet smells of caramel, vanilla and cake lead the way.

The claim to fame of Hans is the delicious sponge cake layered with vanilla cream and strawberries. To get your hands on one, you must arrive before noon, or call to have them save you one. Go earlier and you will find the owners barking rapid Armenian to people over the phone as customers call in to make sure their cake is reserved. The store also sells tarts, an assortment of cookies and cream pastries, but it is their strawberry vanilla cake that makes up for their usually grumpy manners.

Iran pastry shops Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Strawberry cream cake at Hans, Tehran Photograph: The Tehran Bureau

To find good natured folks, Orient Cafe, in what was once Roosevelt Avenue (now Moffateh) is the place to go: a brightly lit, spacious Armenian bakery and cafe, where Mr Sevak and his mother manage day-to-day operations. Their coffee is among the best in the city and the chocolate covered orange slices are always tender and full of flavour. Orient also offers delightful perok, a light apricot cake, and nazook, a crisp Armenian pastry baked here with a walnut filling.

These days, new cafes are sprouting up across Tehran and in an effort to outdo each other, they have introduced elaborate decor, dim lighting, strangely named pastas, or salads with unfamiliar French words. Mr Sevak is old school: “My motto at Orient is, this is not a pasta store, or a salad bar. People should come here for coffee and pastries, plain and simple.”

Orient was established in 1943 by immigrants from Soviet Armenia. Mr Sevak’s family bought the cafe and bakery 15 years ago, following their successful experience with the Anahita Bakery in Sohrevardi Street. His mother oversees the workers in the bakery, and some from the original store were still here until around ten years ago. Bakers serve as the memory of their establishments, learning and perfecting recipes and passing them on.

Many Armenian bakeries also operate as cafes, the most well-known of these being Naderi Cafe, in Jomhoori Street, where generations of writers and artists and students have gathered, and still do. Naderi no longer bakes sweets – but offers raisin cake and roulette (cake roll) brought in. Both always taste stale, but how can you refuse Reza Khan, the jolly waiter, as he insists you’ll enjoy a slice of cake with your coffee?

Iran pastry shops Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Nobel, an Armenian bakery in Mirzayeh Shirazi Street, Tehran, Iran Photograph: The Tehran Bureau

For the best accompaniment to a cup of coffee, you once walked to Nobel, an Armenian bakery in Mirzayeh Shirazi Street, not far from Lord. Opened in 1963, Nobel baked Tehran’s best cream cookie: layer upon layer of light, airy biscuit covered with crème patisserie and their own distinct cookie powder. Nobel also baked sour cherry and peach pies.

But last summer, the store was suddenly replaced by a kallehpazi, a store specializing in kalleh pache, a dish of sheep head and hooves. The male staff of the restaurant told me the owners had sold up and moved to the United States.

So just like that, a monument in Tehran forever disappears. This is not a city where legacies last: they pack up and emigrate.

At least Talaie, another Armenian bakery on Mirzayeh Shirazi Street is still here, next door to the Armenian owned toy and greeting card stores. A small hole-in-the-wall kind of bakery, it sells the best Armenian gata – sweet bread – you can find in Tehran.

Expect long lines at 4 pm when the day’s bread is brought out. Gata is finely layered and in Tehran usually has koritz, a filling of flour, butter and sugar. Nothing goes better with a cup of Turkish coffee than a slice of gata and homemade jam.

Armenians are known not only for their pastries, they opened some of Tehran’s first chocolate shops. In the historic areas of Sadi and Hedayat streets, you will find Mignon bakery and chocolatier. The staff will tell you the shop has been here for 80 years and offer to show you a bound album with pictures of their California stores in Glendale and Pasadena.

The Boghossian family has managed Mignon since 1935, after fleeing to Iran from communist Ukraine where their father was imprisoned – he joined them a few years later. The youngest son, 73-year-old Roben, still runs the Tehran store and can be occasionally found there. My favourite at Mignon is dark chocolate covered marzipan with a hint of orange peel. At Christmas, the store is splendidly decorated and boxes of cakes and chocolates, wrapped in colourful ribbons, are piled everywhere.

To walk into any of these stores is to connect to the old Tehran that we have heard so much of, to scattered remnants of an era largely gone.

“Nobel disappeared overnight,” I complain to the store clerk at Mignon. “I’m terrified that one day I’ll walk to your store and you’ll have left too.”

She smiles and says, in a deep Armenian accent: “Who knows? Maybe. But for now, try to come, we’ll be here.”